Sensory Data

- Senses report raw data

- The raw data is available, but transformed by our filters and interpretations – which happens automatically, because we need to make sense out of things

- Common problems with sensory data

- Most of us do not pay enough attention to the data reaching our various senses

- Sometimes we receive conflicting data (e.g. a person’s words say one thing, and their face, body or tone of voice says another)

- Sometimes we jump to conclusions too quickly, without being aware of the sensory data

- Knowing the above problems, it is useful to test, clarify and alter your interpretations by moving back and forth between the sensory data and your interpretations

Making Sensory Data Statements

- Sense statements describe what you see, hear, touch, taste and smell

- These statements “document” your interpretations

- A good sense statement is specific about time, location, and action or behavior

- The more specific a sense statement is, the more useful

- Sense statements orient the listener(s) to your experience

- Sense statements supply data to what, where, when, how and who – but do not explain why

- Documenting with sense statements is useful because:

- It increases your own understanding of what is happening and clarifies your own interpretations

- It increases the chances of being understood by your audience

- It gives your audience a chance to respond to the same data you are, clarifying interpretations on both sides

- These provide less chance to fall into a “yes I am, no you’re not” argument

- It helps you avoid making global judgments

- I was frustrated because he never answers my questions on time

- She always thinks I’m lazy

- Documenting takes time to do, and sends a message that the person you are communicating with is valued, i.e., worth spending time on

- Documenting with sense statements is particularly useful for giving feedback

- This is true for situations where you want to instigate change

- It is also true for reinforcing behavior that you would like to see continue

- Documenting with sense statements can sometimes be misused to try to prove or to justify

- Avoid using the word “when” by itself in a documenting statement

- Be more specific in terms of time

Interpretations

- Interpretations are the thoughts you have about yourself, others, things, and what happens to you and others (events)

- Interpretations are the meanings you assign in your own head to help you understand yourself, events and other people

- Interpretations happen all the time

- Other names for interpretations

- Impressions

- Ideas

- Beliefs

- Opinions

- Conclusions

- Expectations

- Assumptions

- Stereotypes

- Evaluations

- Reasons

- Interpretations are

- Past history

- What is happening now

- Anticipations of future

- Interpretations depend on

- Sensory information

- Thoughts you have

- Especially beliefs and assumptions

- Immediate feelings

- Wants and desires

- Expectations are prior interpretations affecting your immediate interpretations

- Your interpretations are not based on some “reality” out there

- Interpretations are not “the way things are”

- It is useful to keep your interpretations tentative

- Many different interpretations are available for the same sensory data

- Often, too little sensory data is available to make a firm interpretation

- Because people are often uncomfortable with not knowing, the temptation is there to jump to conclusions

- Often the sensory data in a given situation is incomplete

- Sometimes sensory data conflicts with previous experiences or assumptions

- This leads to misinterpretations

- The sensory data in a situation may be new to you

- Keeping open to additional sensory data retains the possibility of seeing things in a new way, i. e. of learning

Feelings

- Feelings are spontaneous responses to your interpretations and the expectations you have

- Emotional responses are inside your body, but may have outward signs

- For example, when angry, you may notice this by tense muscles, loud rapid speech, or flushed skin

- You may notice sadness by moist eyes or tears

- You may notice elation by smiles, laughing or joking

- Feelings typically exist on a spectrum, e.g.

- Annoyed, irritated, angry, enraged

- Anxious, nervous, fearful, terrified

- Liking, affectionate, loving, passionate

- Pleased, happy, elated, jubilant

- Feelings are you, part of the person you are

- Feelings also serve as a barometer

- Emotions can alert you to what’s going on

- Emotions can help you understand your reaction to a situation

- Emotions can alert you when two people have different interpretations

- Feelings can help you clarify your expectations

- Some feelings arise because of differences between what you expected and what actually happened

- For example, if you expected to have your proposal accepted, and it was rejected, you would likely feel surprised, hurt, and disappointed

- If you expected to have your proposal rejected, and it was accepted, you might feel happy, excited or gratified

- Sometimes you don’t know what you expect, but can determine expectations after the fact by what you felt in response to a situation

- Some feelings arise because of differences between what you expected and what actually happened

- How do you bring feelings into your awareness?

- Watch for physiological signs

- Sweating, rapid heartbeat, lightness

- Watch for behavioral signs

- Avoiding eye contact, becoming quiet, laughing

- Watch for physiological signs

- If you notice subtle feelings, let yourself amplify the feeling by focusing awareness on the subtle feeling

- Noticing what you are feeling is difficult sometimes because we often feel more than one feeling at a time

- It’s easier when we’re feeling only one emotion

- You might, for instance, feel cautious, irritated and contentious all at the same time

- In these cases, it’s easy to send out mixed messages

- Give up the myth that you can ignore or control your feelings – you can control actions and are responsible for those

- Trying to control your feelings actually turns over control

- Avoiding paying attention lets your feelings take over

- Feelings seem to want to express – numbing to them forces the feelings to build up until they break through – and you have lost control

- When we consciously try not to express feelings, our bodies express feelings anyway – and often in ways that are less clear

- Trying to control your feelings actually turns over control

- Making Feeling Statements

- Pick your time and place

- Own the feelings expressed as yours

- When this happens, I feel . . .

- Feelings can be expressed powerfully non-verbally, but that leaves room for misinterpretation

- Words added to actions can clarify, e.g., is a smile being happy or is it being nervous?

- Mixed feelings can also be stated, which helps to let people know what your experience is – otherwise they are likely to be confused

- Obstacles to making feeling statements

- It is difficult to recognize your own feelings

- It may feel uncomfortable to verbalize your feelings – it’s not encouraged by our culture

- It seems risky to verbalize your feelings

- You make yourself vulnerable to rejection, or to being seen as weak, silly, or unusual

- You may be in the habit of substituting opinions, evaluations, or questions for statements of feelings

- “You have no right to say that!” when you mean, “I feel sad when you say that”

- “You shouldn’t work so late so often”, when you mean, “I feel lonely. I miss you”

- Adding appropriate feeling statements can take a dull meeting or situation and make it much more interesting

- People usually pay more attention, and become more engaged, when feelings are acknowledged

- The amount of risk-taking a person is capable of is usually related to the degree of self-esteem a person has

- Making disclosing statements (of feelings, interpretations, and what you want) does pay off

- Besides risking rejection, you also open the opportunity for acceptance

- What we think is being kept hidden or private is often seen anyway, but seen in distorted ways

- Disclosing significantly increases trust

- Disclosing also clarifies your own situation

- You can also choose to disclose a step at a time, starting small

- When you think you are misunderstood is an ideal time to disclose, or if you think that you are misunderstanding someone else

Intentions or Wants

- Examples of intentions

- To approach, to reject, to support, to persuade

- To be funny, to ignore, to clarify, to avoid

- To cooperate, to praise, to defend self, to hurt

- To be friendly, to ponder, to help, to accept

- To demand, to be honest, to conceal, to play

- To explore, to be caring, to listen, to disregard

- To share, to understand, to be responsive

- Intentions can span time frames

- In our usage, focus on intentions as near term desires – what do you want to happen in a specific situation

- One obstacle to identifying your own intentions is that we often think much more on what it is we want others to do

- If this is the case, your intentions come out in the form of commands or questions

- You should finish the job as soon as possible, instead of I would like you to finish soon

- Would you like to give me this report tomorrow, instead of I’d like you to give me the report tomorrow

- You shouldn’t do that, instead of I want you to stop doing that

- If this is the case, your intentions come out in the form of commands or questions

- Often intentions can be or become hidden agendas

- You may be unaware of all your intentions at times

- You forget them, or think they are too unimportant to mention

- You choose to keep your intentions hidden on purpose

- If your intention is to get even, or to be admired, or to hurt, you may not want these types of intentions to become known

- Sometimes hidden agendas happen because I have not thought through what it is that I want

- It is important to discern between preferences and demands

- Stating wants as preferences allows others to be open to negotiation, rather than defending against demands

- Intentions have a big impact on your actions

- Changing intentions can have a bigger impact on what you do than trying to change actions

- It is useful to think of intentions as organizers

- Thinking about intentions helps you expand possibilities by needing to think about what you want and don’t want

- You can learn more about what your intentions are by examining your actions

- Usually there is something you wanted by doing things, or liked doing

- Feelings can tell you about your intentions as well

- Feeling positive, OK, or satisfied indicates that your intentions and your actions and behaviors usually match

- Feeling irritable or unhappy is a clue that your major intentions are not matching your behaviors

- A third way of learning about your own intentions is to ask yourself what is it that I want that I’m not telling people or not willing to admit?

- Intention statements are ways of being direct about what you want to do or want not to do

- “Might”, “could”, or “maybe” when used in intention statements confuse and hide your intentions

- In competitive negotiations, you may want to deliberately obscure what you want

- In cooperative work situations, being indirect with what you want wastes time and increases problems

- Intentions, like feelings, can be in conflict inside yourself

- Disclosing these conflicting intentions can still be valuable

- Helps clarify for yourself what is most important

- Clarifies the range of possibilities for your audience

- Disclosing these conflicting intentions can still be valuable

Negotiations

- One fundamental principle of successful negotiations is to avoid arguing about conclusions or end-positions and to concentrate on discussing what is important to each side

- The communication skills training equivalent of doing this is to spend a lot of time in documenting interpretations by sense statements and to think through and articulate what you want not in terms of end-positions, but rather in terms of what has meaning to you

- Question your interpretations, and make sure you verbalize them and check with the other party to verify that they share the same understandings

- Verbalizing what you prefer and what you are willing to do in order for this to happen will often move a negotiation forward

Actions, or What I am Willing to Do

- Action statements put words to your behavior in simple descriptive ways

- I will, I am, I was, etc.

- Paying attention to actions can provide self-information

- Actions can contradict what we say

- Dropping volume at end of sentence, fidgeting with glasses, or walking around while talking can indicate lack of confidence, for instance

- Getting in habit of observing actions versus statements will identify patterns of behavior that you may want to change

- Actions can contradict what we say

Actions

- Stating what you are willing to or going to do increases clarity

- It’s not obvious what you are doing, even if you think it is

- Saying “I’m thinking about what you said” avoids misinterpretation for why you are looking around or vacantly staring, for instance

- Action statements let people know you are aware of your actions and of the meanings you place on them

- Saying “I interrupted you” indicates self-awareness plus caring about effect you have on others

- “I’m having trouble concentrating. I’m still thinking about a conflict that happened an hour ago. I’m sorry” lets your audience know that you probably are placing a different meaning on what’s happening than they might guess from your being distracted

- Action statements about the future are commitments

- Saying “I will …” lets people know what you are willing to do or not willing to do

- This lets people know what to expect from you

- Keeping your commitments or renegotiating when unable to keep commitments is the foundation for building trust

- Trust is the single most important factor in having and maintaining good communication

- Stating what you are willing to do opens the space for the other person to offer to do something as well

- If communications or negotiations are stuck, this often moves the process forward

Speaking for Self

- Fundamental skill for all communications

- By speaking for yourself, you identify you as the source of your awareness

- By reporting your own interpretations, thoughts, feelings, wants, desires, and intentions, you indicate that you are the owner

- “I think …”, “I feel …”, “I am willing to ….”, “I want …,” you identify yourself as the source of your awareness

- Speaking this way acknowledges that you are not expert on what your coworkers think, feel, want and intend

- This means using “I, me, my and mine”, which some of us are conditioned to believe means being selfish or self-centered

- This does indicate self-confidence and belief in self

- High self-esteem is a positive trait

- Speaking for self statements take responsibility

- “Under-responsible” statements substitute it, one or some people for “I”, or include no pronoun or reference at all

- Examples of under-responsible statements

- He doesn’t listen

- It would be a good thing if some people here would change

- There’s nothing anyone can do about this mess

- Under-responsible statements force you to guess at the opinions, intentions or feelings of the person, since they are understated

- Constant use of under-responsible statements can cause the opinions, thoughts and wants of the speaker to be continually devalued, since the speaker does not claim the content of what is spoken

- Over-responsible statements speak for others

- You should always call the customer and not just email, because you like direct contact

- All men are like that

- You don’t understand why I prefer to talk that way

- Over-responsible statements substitute we, you, everybody, or all for “I”, and frequently contain “should” and “ought to”

- Many of us resent being spoken for and close down to the rest of what the over-responsible speaker says

- Making Interpretive statements is a skill

- Interpretive statements carry more weight if they are “documented” by sensory statements

- By making clear your interpretations, you make explicit what you are thinking, and this moves the communication forward

- Examples of interpretive statements

- I think we should take a break now

- I expect to be on time to the meeting

- It seems like you are worried about whether we are prepared for our customer meeting

- I’m wondering if you have come to the same conclusions I have

- I think it likely that sales will never change

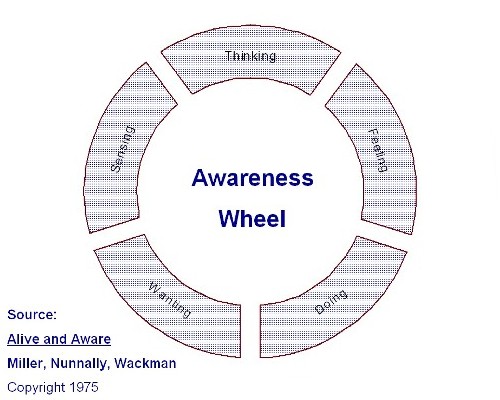

Putting the Awareness Wheel to Work

- Dialogue involves other people, and works well when you have:

- Self-awareness of Awareness Wheel categories

- Support for others to identify and express their own awareness

- Ability to accurately hear what others’ say and express

- You can work through the Awareness Wheel categories imagining what someone else is trying to say

- This will lead to uncovering gaps in what’s expressed

- Will often surface the need to check interpretations or sensory data

- Checking with other person will move the communication forward

- Particularly useful if you notice incongruities

- Between sensory data and interpretations, actions and words, your feelings and the situation, etc.

- Particularly useful if you notice incongruities

- Checking with others is easy – add a who, what, when or where question to the person’s Awareness Wheel categories

- Who do you want to include?

- What do you think?

- What are you doing?

- Where did you hear that?

- How do you feel?

- Why or closed questions are best avoided

- “Don’t you think it would be better if we both went?” is a closed question, and it disguises “I want to go with you”

- Why questions lead to blame, are difficult to answer, and rarely move the communication forward

Negotiation Tips

- Negotiations proceed better when desires are stated as preferences, not demands

- Demands mean you are fixed on the outcome, that it must be your way

- Preferences are indications of what you want without predetermined outcomes

- Communicating your willingness to do other things than your own preferences leads to open negotiations and more flexibility